In September, we hosted Material World – our third pop-up exhibit at the beautiful MacDonald House heritage home in Vaughan. It has taken months for us to consider, reflect, and process the theories and ideas about learning and living that emerged during this incredible exhibit. We begin by inviting you to read the entry below, submitted by artist/educator-in-resident, Lisa Nackan. In this guest-post, Lisa eloquently describes the materialization of her installation and shares art therapy wisdom and deeply personal connections from her collaborative experience at Material World.

Guest post by Lisa Nackan

Brainstorming with Aviva and Simone

When you allow your imagination free reign to explore themes and ideas, thought and fantasy, something happens and one + one + one = something far greater than just three. And you hit upon that “aha” moment when the idea is just right and you all know it, not just in a knowing kind of way, but you can feel it viscerally, and it pumps up your heart and your eyes start to glow.

Exploring the venue

Perhaps it was the magic surrounding the Group of Seven, or the name of the painting that transpired from the tangled garden, or perhaps it was the building with aged secrets hidden within the walls, but I fell in love with the MacDonald House. (Simone and Aviva were already captivated.) The trees whispered outside, their images emblazoned through the opened windows, coming into the space, the sunlight reaching into all the rooms, tiptoeing on the hardwood floors. I could see the installation vividly in the room at the top of the stairs, even when the room was still empty.

Brainstorming with Aviva and Simone

When you allow your imagination free reign to explore themes and ideas, thought and fantasy, something happens and one + one + one = something far greater than just three. And you hit upon that “aha” moment when the idea is just right and you all know it, not just in a knowing kind of way, but you can feel it viscerally, and it pumps up your heart and your eyes start to glow.

Exploring the venue

Perhaps it was the magic surrounding the Group of Seven, or the name of the painting that transpired from the tangled garden, or perhaps it was the building with aged secrets hidden within the walls, but I fell in love with the MacDonald House. (Simone and Aviva were already captivated.) The trees whispered outside, their images emblazoned through the opened windows, coming into the space, the sunlight reaching into all the rooms, tiptoeing on the hardwood floors. I could see the installation vividly in the room at the top of the stairs, even when the room was still empty.

Weaving a web…

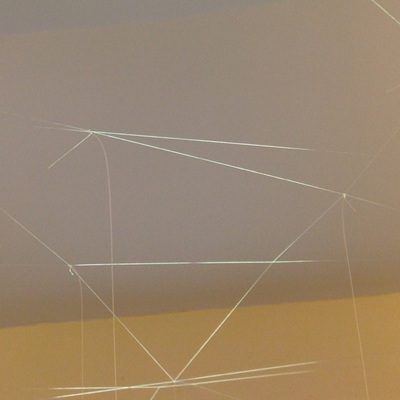

The concept of a perceptible, interconnected humanity gave rise to the creation of a fishing gut web hanging from the ceiling, barely detectable, like spider web, yet extremely strong and resilient.

Spiders often trigger a fear response and are associated with a deep aversion. Some people don’t want to even look at them. Sometimes they simply can’t. We all have a dark side to our own personalities, just like this - a side that is perhaps repressed, always more difficult to look at or acknowledge.

And yet these sometimes undesirable but magnificently fascinating creatures build webs in order to survive. The webs are sometimes seen and sometimes unseen. Spiders catch their food in these intricate nets that they create, and balance along the threads watching and waiting.

Making the invisible visible can nourish us. Not in the same way as a spider devours its prey, satisfying its appetite, but rather with a recognition of something that is uniquely ours… a letting free of our selves, as they truly are, and when this knowing comes with acceptance, and compassion, this can nourish our souls, in a deeply meaningful and life-changing way.

Tendrils

We hung fishing line tendrils from the woven, almost transparent web that was just within our reach, placing pieces of different lengths in a haphazard and spontaneous way. And then after it was all done, and I was back at home, Aviva created the first representation, in the centre of the room, and sent me a photograph that thrilled me. I knew that she had thoughtfully placed her formation in the exact spot where it would be framed by the open door, becoming a flirt for people walking upstairs, drawing them in.

The concept of a perceptible, interconnected humanity gave rise to the creation of a fishing gut web hanging from the ceiling, barely detectable, like spider web, yet extremely strong and resilient.

Spiders often trigger a fear response and are associated with a deep aversion. Some people don’t want to even look at them. Sometimes they simply can’t. We all have a dark side to our own personalities, just like this - a side that is perhaps repressed, always more difficult to look at or acknowledge.

And yet these sometimes undesirable but magnificently fascinating creatures build webs in order to survive. The webs are sometimes seen and sometimes unseen. Spiders catch their food in these intricate nets that they create, and balance along the threads watching and waiting.

Making the invisible visible can nourish us. Not in the same way as a spider devours its prey, satisfying its appetite, but rather with a recognition of something that is uniquely ours… a letting free of our selves, as they truly are, and when this knowing comes with acceptance, and compassion, this can nourish our souls, in a deeply meaningful and life-changing way.

Tendrils

We hung fishing line tendrils from the woven, almost transparent web that was just within our reach, placing pieces of different lengths in a haphazard and spontaneous way. And then after it was all done, and I was back at home, Aviva created the first representation, in the centre of the room, and sent me a photograph that thrilled me. I knew that she had thoughtfully placed her formation in the exact spot where it would be framed by the open door, becoming a flirt for people walking upstairs, drawing them in.

The room

Within two days the web had transformed from a network of invisible threads, to a colourful, moving, collection of sacred images of the self — made visible. I felt humble entering into that space and when I finally created my own image, and hung it towards the window, I watched it move as though it were perusing a new environment, finding its place amongst the others.

Within two days the web had transformed from a network of invisible threads, to a colourful, moving, collection of sacred images of the self — made visible. I felt humble entering into that space and when I finally created my own image, and hung it towards the window, I watched it move as though it were perusing a new environment, finding its place amongst the others.

| | Seeing what was made visible We sat in a group on the wooden floor, scrutinizing the installation. Silence, then words and feelings and descriptions. Visibility. Community. Conversation. Strength. Beauty. We placed fans on either side of the room, representing the invisible forces that move us, forces that compel us to re-adapt, perhaps transform. Society One of the participants, uncomfortable and agitated, couldn’t find a place of comfort in the room. When I spoke to her, she told me that she didn’t like the movement. I think the room was too unpredictable and I suggested that she create something, so we went together to the materials. Immersed in baskets of colours, textures, shapes, and symbols, she began to construct. And it was more than the medley of objects that she wove into the fishing gut, she became comfortable, she smiled, she explored the room in a different way. I was able to watch something unfold on a deep, metaphorical level. |

She spoke as she worked long after her hanging representation was made, gathering long pieces of ribbon and tying it around groups of the installations, telling us that sometimes people don’t belong and aren’t part of things, and sometimes people have to stay out. She showed us visually how inclusion and division are part of the way society works. And the interesting thing was that suddenly the installation didn’t look as appealing to me any longer. There was a contained chaos, and I had to remind myself that this was NOT my creation, but a community installation that had to take its own journey. But something about the divisiveness that now split the room made me uncomfortable and I left to go home with my thoughts in disarray.

I wasn’t the only one. When I returned, somebody had taken away those ribbons dividing the space.

I wasn’t the only one. When I returned, somebody had taken away those ribbons dividing the space.

Outsider Witness

Despite the fact that the room drew many people in, and that there was something ethereal about the swaying, and the colour, and the way the light trickled into that space, the shadows and prisms on the wall… I felt as though something wasn’t complete. We had made the invisible visible. But something tugged at me inside and I knew that there was something more we had to do…

And then it occurred to me as if it were the most obvious thing in the world. We needed a connection. We needed the creations to be seen in more than a visual way. They needed to be experienced and felt. There had to be some kind of communication between the seer and that being seen. In narrative therapy they call that outsider witness, an experience in which somebody witnesses, acknowledges, reflects on the experience or event – in this case, the creation – helping to give it a deeper sense of meaning.

So, we began symbolic conversations that we placed underneath the creations. And it was then that the installation, that this profound journey, felt complete.

Despite the fact that the room drew many people in, and that there was something ethereal about the swaying, and the colour, and the way the light trickled into that space, the shadows and prisms on the wall… I felt as though something wasn’t complete. We had made the invisible visible. But something tugged at me inside and I knew that there was something more we had to do…

And then it occurred to me as if it were the most obvious thing in the world. We needed a connection. We needed the creations to be seen in more than a visual way. They needed to be experienced and felt. There had to be some kind of communication between the seer and that being seen. In narrative therapy they call that outsider witness, an experience in which somebody witnesses, acknowledges, reflects on the experience or event – in this case, the creation – helping to give it a deeper sense of meaning.

So, we began symbolic conversations that we placed underneath the creations. And it was then that the installation, that this profound journey, felt complete.

My story

The wrangle between invisibility and visibility has been a preoccupation of mine for most of my life. As a reticent and painfully shy child, I was virtually invisible. I grew up in the shadows of everything that seemed louder and bigger and better and more visible than I ever could be. I barely spoke at school, did as I was told, and growing up in South Africa during the era of “children should be seen and not heard”, realized quickly that it felt safer if I behaved in a way that would ensure that nobody paid much attention to me. And nobody did.

Many people have a “public self” and a “private self”. For me, the “public self” was this barely discernible vision of a waif of a child and the “private self” was the colorful, limitless, pained, unstoppable, crazed reality that resided only in the confines of my head.

My invisibility was both a burden and a blessing. Being unseen felt safe but it also meant that truly being me was never acknowledged. Nobody was permitted in to share my experiences. There was no mirror in which I could ruminate about an objective view of my thoughts.

There is a continual draw between the safety of invisibility, and the pain of being unseen, and the power of visibility, and the vulnerability that goes with that. This conflict still tortures me – and I don’t use that word lightly. Torture is extreme anguish, and that tug-of-war taunts me – in my thoughts, my writing, my behavior, my history, and even in my dreams. I have noticed that when I paint, the canvas becomes a medley of layers, some seen and some unseen. I cannot merely paint a picture. The image needs an undercoat of complimentary colours that might show through, and then more layers of movement and texture. And this wasn’t conscious. I was painting me, regardless of the image. And I noticed this with a sense of wonder and admiration of what wisdom the unconscious mind holds.

There is something in seeing the unseen that is so profound. As an Art Therapist I bear witness to this unfolding. The unseen sometimes has no words, but simply resides in images or metaphor. When it emerges it begins to exist in a different way. When something is perceptible, you can begin to relate to it. Communication can happen. When communication happens, so does connection. And we as human beings are wired in the most primal way – we need connection in order to survive. When you are invisible, you exist in a void. Visibility means that your presence is more tangible. When you are invisible, nobody can gain access to your heart. Truly.

I strive to be conscious of the way I interact with people whose lives touch mine and this awareness profoundly marks the way I work as an Art Therapist because you cannot be attuned with somebody if you cannot gain access into their heart.

Dr. Jonice Webb, in her book, Emotional Neglect, writes about something she has called “a fatal flaw”, in which people hold onto a secret shame, believing that there is something wrong with them, something that cannot be exposed, and because of this corrupted belief, hide their true selves. Dr. Webb explains how the suffering caused by this secret and incorrect belief “takes its toll and erodes the bedrock of existence.”

Invisibility was my fatal flaw. I didn’t want anyone to see the real me because I believed that I was too different from everyone else, that there was something wrong with being a silent, perceptive, sensitive child. I didn’t want to be rejected by anyone, so I rejected the world instead.

I have learned that invisibility has beauty when you begin to see it, and then it can go by another name. You don’t actually “see” this coming into being but it is rather a beauty that you feel, perhaps a compassionate stirring of the soul that you experience from the pure authenticity of somebody acknowledging and witnessing simply what is. My work has shown me how powerful and gratifying an expression of the true self can be.

The wrangle between invisibility and visibility has been a preoccupation of mine for most of my life. As a reticent and painfully shy child, I was virtually invisible. I grew up in the shadows of everything that seemed louder and bigger and better and more visible than I ever could be. I barely spoke at school, did as I was told, and growing up in South Africa during the era of “children should be seen and not heard”, realized quickly that it felt safer if I behaved in a way that would ensure that nobody paid much attention to me. And nobody did.

Many people have a “public self” and a “private self”. For me, the “public self” was this barely discernible vision of a waif of a child and the “private self” was the colorful, limitless, pained, unstoppable, crazed reality that resided only in the confines of my head.

My invisibility was both a burden and a blessing. Being unseen felt safe but it also meant that truly being me was never acknowledged. Nobody was permitted in to share my experiences. There was no mirror in which I could ruminate about an objective view of my thoughts.

There is a continual draw between the safety of invisibility, and the pain of being unseen, and the power of visibility, and the vulnerability that goes with that. This conflict still tortures me – and I don’t use that word lightly. Torture is extreme anguish, and that tug-of-war taunts me – in my thoughts, my writing, my behavior, my history, and even in my dreams. I have noticed that when I paint, the canvas becomes a medley of layers, some seen and some unseen. I cannot merely paint a picture. The image needs an undercoat of complimentary colours that might show through, and then more layers of movement and texture. And this wasn’t conscious. I was painting me, regardless of the image. And I noticed this with a sense of wonder and admiration of what wisdom the unconscious mind holds.

There is something in seeing the unseen that is so profound. As an Art Therapist I bear witness to this unfolding. The unseen sometimes has no words, but simply resides in images or metaphor. When it emerges it begins to exist in a different way. When something is perceptible, you can begin to relate to it. Communication can happen. When communication happens, so does connection. And we as human beings are wired in the most primal way – we need connection in order to survive. When you are invisible, you exist in a void. Visibility means that your presence is more tangible. When you are invisible, nobody can gain access to your heart. Truly.

I strive to be conscious of the way I interact with people whose lives touch mine and this awareness profoundly marks the way I work as an Art Therapist because you cannot be attuned with somebody if you cannot gain access into their heart.

Dr. Jonice Webb, in her book, Emotional Neglect, writes about something she has called “a fatal flaw”, in which people hold onto a secret shame, believing that there is something wrong with them, something that cannot be exposed, and because of this corrupted belief, hide their true selves. Dr. Webb explains how the suffering caused by this secret and incorrect belief “takes its toll and erodes the bedrock of existence.”

Invisibility was my fatal flaw. I didn’t want anyone to see the real me because I believed that I was too different from everyone else, that there was something wrong with being a silent, perceptive, sensitive child. I didn’t want to be rejected by anyone, so I rejected the world instead.

I have learned that invisibility has beauty when you begin to see it, and then it can go by another name. You don’t actually “see” this coming into being but it is rather a beauty that you feel, perhaps a compassionate stirring of the soul that you experience from the pure authenticity of somebody acknowledging and witnessing simply what is. My work has shown me how powerful and gratifying an expression of the true self can be.

Lisa Nackan 'becoming visible' | photo: Elana Emer

Lisa Nackan 'becoming visible' | photo: Elana Emer Making the invisible visible seemed a significant topic to explore as both Art Therapist, and once silent child. As an experiential, creative, play-based activity, the subject felt universal and accessible to everyone. Although the idea for this installation is seemingly simple, it somehow reaches down into the depths of our collective unconscious.

What I love most about Art Therapy is the belief there is no right way and no wrong way to create something. There is only your way. When you are able to expose yourself, safely unmasking all those complications we hide behind, it is possible, through becoming visible, to allow validation and individuality, authenticity and connection to ensue. And there is a moment of profound wisdom in that vulnerable moment when the disguise is removed.

What I love most about Art Therapy is the belief there is no right way and no wrong way to create something. There is only your way. When you are able to expose yourself, safely unmasking all those complications we hide behind, it is possible, through becoming visible, to allow validation and individuality, authenticity and connection to ensue. And there is a moment of profound wisdom in that vulnerable moment when the disguise is removed.

>> Find out more about Lisa Nackan and her incredibly inspiring work

>> Read about other artists and educators we've collaborated with

>> Apply to our Artist/Educator-in-residence program

>> Visit our Playbill page and subscribe to our mailing list (below) to find out where we'll pop up next

>> Read about other artists and educators we've collaborated with

>> Apply to our Artist/Educator-in-residence program

>> Visit our Playbill page and subscribe to our mailing list (below) to find out where we'll pop up next

RSS Feed

RSS Feed